The Matryoshka Dolls of Modern Networking: A Technical Evolution

The Matryoshka Dolls of Modern Networking: A Technical Evolution

Introduction: The Internet is a Lie

If you think the internet is a flat, happy place where your computer talks directly to a server, I have bad news for you: The internet is a lie.

Modern networking is fundamentally a history of deception. We want the logical freedom to move things around without the physical reality of moving cables. To achieve this, we turned to the “Matryoshka Doll” strategy (Russian nesting dolls). We take a packet, wrap it inside another packet, and sometimes when we are feeling particularly chaotic wrap that inside a third packet.

It’s an illusion of infinite connectivity built on top of a physical reality that is rigid, hierarchical, and frankly, a pain in the ass to wire.

Today, we are going to look at how we went from manual spreadsheets to the hyper-programmable, kernel-bypassing insanity that runs the cloud today.

Part 1: A Brief History of “Why We Did This”

To understand why we complicate things with overlays, you have to understand the nightmare we were waking up from.

The Villain: The Number 4,096

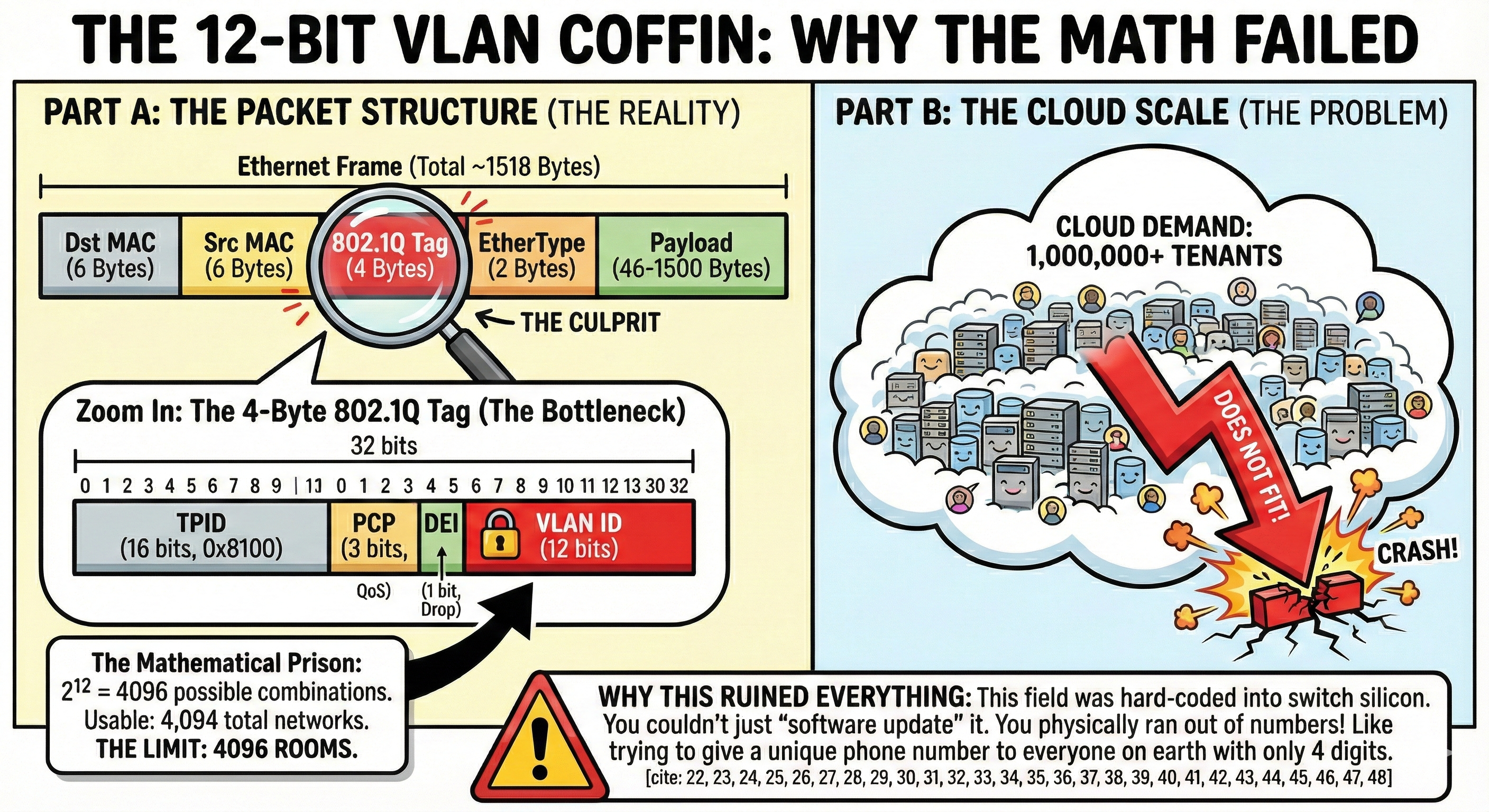

In the old days (pre-2010), if you wanted to separate two departments (say, HR and Engineering), you used a VLAN (Virtual Local Area Network).The IEEE 802.1Q standard gave us a 12-bit identifier for VLANs. If you do the math (2^12), that gives you 4,096 possible segments.For a university campus? Fine. For a cloud provider trying to host 1,000,000 customers? Catastrophic.

# The mathematical impossibility of early cloud networking

max_vlans = 4094

cloud_tenants_needed = 1000000

coverage = (max_vlans / cloud_tenants_needed) * 100

print(f"We can only support {coverage:.2f}% of our customers.")

# Result: The CEO fires everyone.

The $500,000 Rack Problem

Before overlays, an IP address wasn’t just a number; it was a physical location. IP 10.1.1.5 meant “Row 4, Rack 2, Switch Port 12.”

If you wanted to move a Virtual Machine to a different server with a different subnet, you had to change its IP address. This broke the application. The alternative? Network engineers physically rewiring switches to extend Layer 2 domains across the data center. This resulted in “Spanning Tree” loops that would occasionally take down the entire banking sector for an afternoon.

We needed a way to let the logical network (the VM) float above the physical network (the cables). Enter the Overlay.

Part 2: The Modern Era (What We Actually Use)

We stopped trying to fix the physical network and decided to just hide it. Today, almost every packet you send in the cloud is encapsulated. Let’s look at the two heavyweights running the world right now.

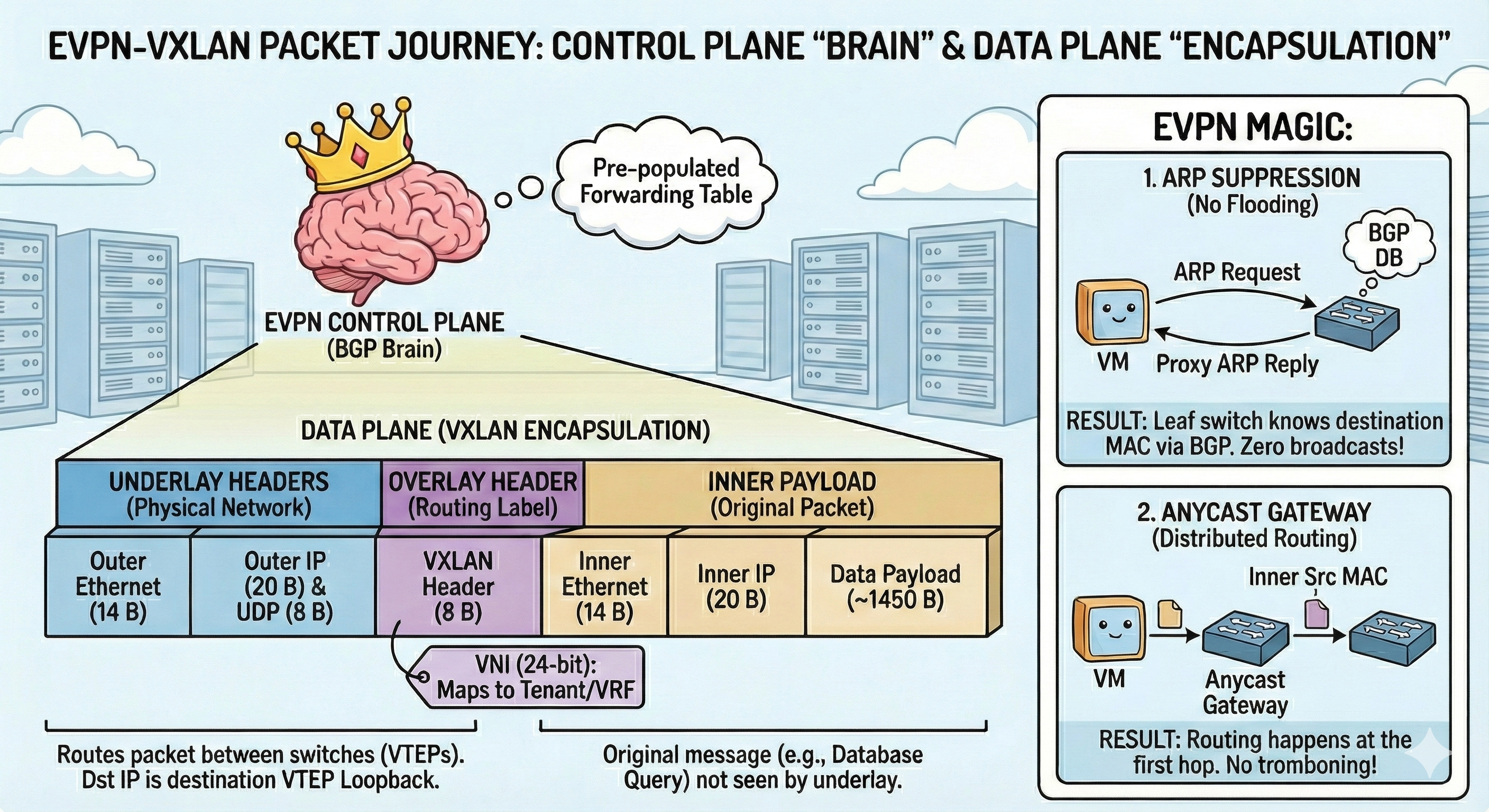

1. EVPN-VXLAN: The Enterprise Workhorse

Used by: 80% of Fortune 500 Data Centers, Banks, Telecoms.

Used by: 80% of Fortune 500 Data Centers, Banks, Telecoms.

VXLAN (Virtual Extensible LAN) solved the “4,096 problem” by giving us a 24-bit ID. That’s 16 million segments. Enough for everyone to have their own private party.

But VXLAN had a dumb control plane. It used “Flood and Learn” essentially shouting, “WHO HAS MAC ADDRESS AA:BB:CC?” to every switch in the building.

The Fix: We married VXLAN to BGP EVPN. Instead of shouting, switches now whisper to each other using BGP (the protocol that runs the internet).

- Switch A: “Hey, just so you know, I am hosting the HR Web Server now.”

- Switch B: “Cool, I’ll update my routing table. Thanks.”

This eliminated the flooding and made the network stable enough for JP Morgan to trade billions of dollars on it.

2. Geneve + eBPF: The Cool Cloud Kids

Used by: Kubernetes (Cilium), AWS (Nitro), Service Meshes.

Used by: Kubernetes (Cilium), AWS (Nitro), Service Meshes.

VXLAN is great, but its header is fixed. You can’t add notes to it. Modern cloud apps need to say things like, “This packet is from the Frontend, it has a Security Clearance of Level 5, and it prefers to avoid the slow router.”

The Fix: Enter Geneve (Generic Network Virtualization Encapsulation). It has a variable-length header, meaning we can shove metadata into the packet itself. Combined with eBPF (extended Berkeley Packet Filter), we can now program the Linux kernel to read these headers and make decisions before the packet even hits the heavy parts of the Operating System.

3. AWS Nitro (The Hardware Way)

Used by: AWS (obviously), and copied by everyone else (IPUs/DPUs).

Used by: AWS (obviously), and copied by everyone else (IPUs/DPUs).

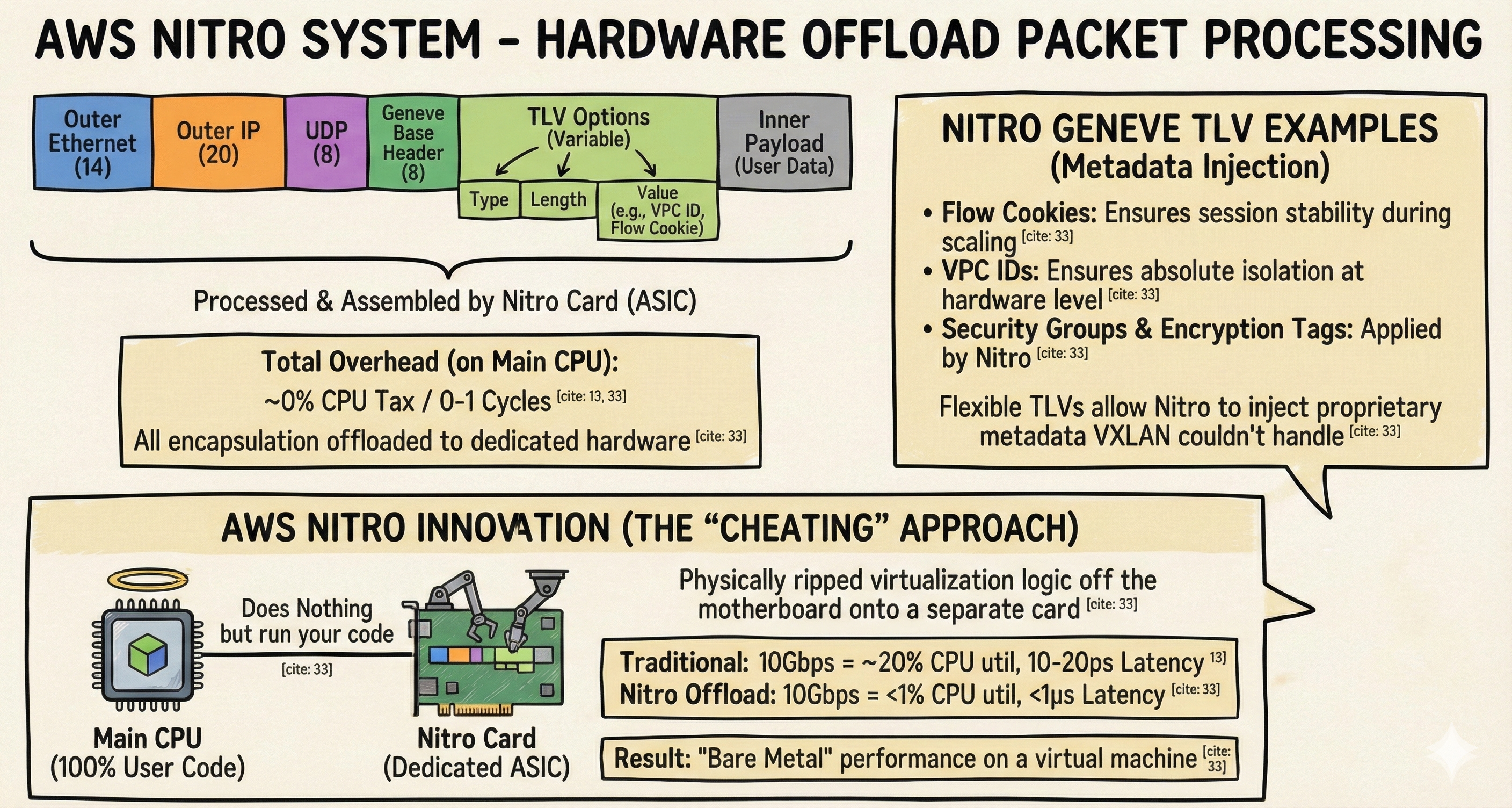

While Spotify and Kubernetes developers were busy optimizing software with eBPF to save CPU cycles, Amazon took a different approach: They just built better hardware. The AWS Nitro System solves the “Matryoshka Tax” by cheating.

How It Works:

Amazon realized that if the main CPU has to spend 20% of its time wrapping packets in Geneve headers, the customer gets angry because they are paying for a 100% CPU and getting 80%. So, they physically ripped the virtualization logic off the motherboard and put it on a separate card (the Nitro Card).

- The Main CPU: Does nothing but run your code

- The Nitro Card: Handles the VPC networking, encryption, storage, and security groups.

- The Impact: You get “Bare Metal” performance on a virtual machine. The encapsulation still happens—the Matryoshka doll is still there but it’s being assembled by a dedicated robot (ASIC) on the side, not by your main CPU.

- Why AWS Loves Geneve: AWS switched from VXLAN to Geneve specifically for this hardware. The flexible “Type-Length-Value” (TLV) headers allow the Nitro card to inject metadata that VXLAN couldn’t handle, such as:

- Flow Cookies: To ensure your session doesn’t break when a load balancer scales.

- VPC IDs: Ensuring absolute isolation at the hardware level.

4. Disaggregated Core: The “IKEA” Router

Used by: AT&T (DriveNets), Major ISPs, Hyperscalers.

Used by: AT&T (DriveNets), Major ISPs, Hyperscalers.

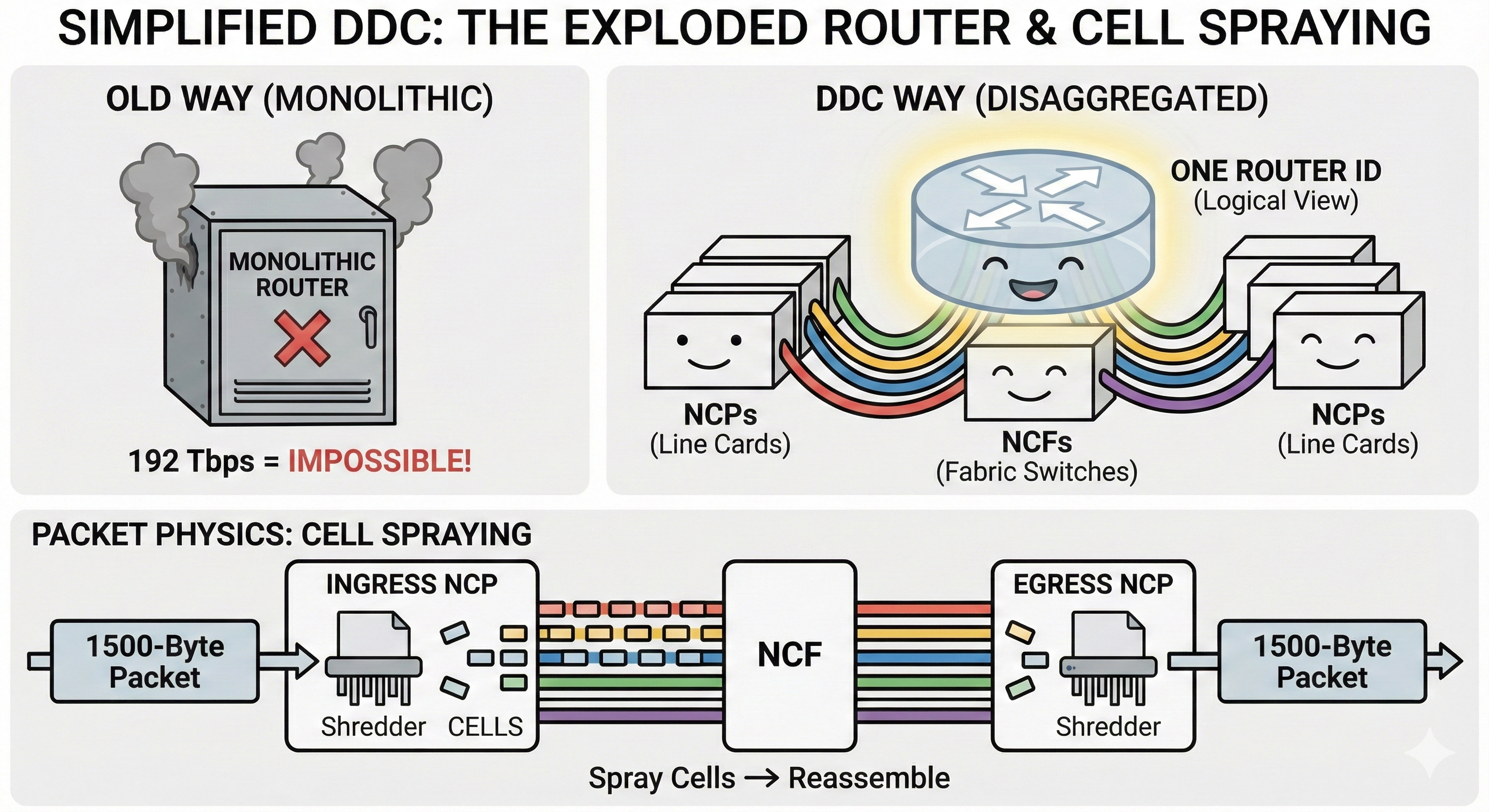

For decades, if you wanted to be an ISP like AT&T, you had to buy a “Router Chassis.” This was essentially a refrigerator-sized metal box that cost more than a house, sold by a vendor who locked you into their proprietary ecosystem forever. If you needed more ports? You had to buy a new fridge.

The Revolution:

The “Lego” Approach (DDC) AT&T looked at these giant metal fridges and said, “No thanks.” They moved to Distributed Disaggregated Chassis (DDC) architecture using DriveNets.

Instead of one giant proprietary machine, they built a “router” out of standard, cheap white-box switches connected by cables.

The Architecture (Deconstructed): They broke the router into three generic pieces, like a kit of parts:

- The Brain (Control Plane): Standard x86 servers running the routing software in containers.

- The Ports (NCPs): “Pizza Box” switches (using Broadcom Jericho chips) that plug into the outside world.

- The Fabric (NCFs): “Pizza Box” switches (using Broadcom Ramon chips) that just glue the other boxes together.

Why It Wins:

It acts exactly like Kubernetes for Networking.

- Need more bandwidth? Don’t buy a new chassis. Just plug in another “Pizza Box” (NCP).

- Need more throughput? Plug in another Fabric box (NCF).

- Scale: This system scales to 192 Tbps. That is a “distributed cloud of white boxes” pretending to be a router.

Part 3: The Anatomy of a Modern Packet

(Or: Why your MTU settings are ruining your life)

This is where the “Matryoshka Doll” analogy gets real. If you capture a packet flying through a Kubernetes cluster or AWS VPC, you are looking at a Russian nesting doll of headers.

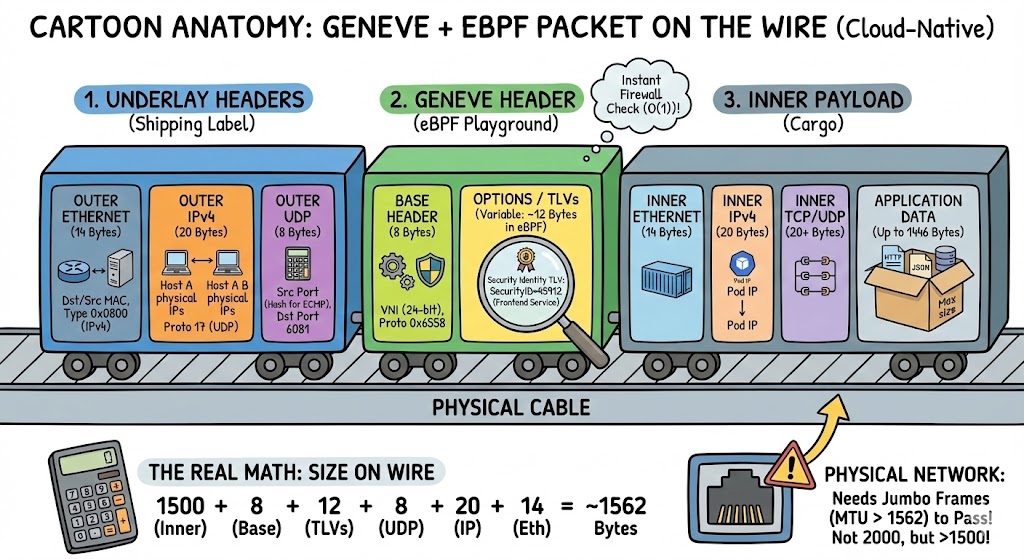

Let’s dissect a Geneve packet byte-by-byte.

The “Doll” Breakdown

Layer 1: The Delivery Truck (The Underlay)

This gets the packet from Physical Server A to Physical Server B. The switches only look at this.

- Outer Ethernet (14 Bytes): Source and Destination MAC of the physical servers.

- Outer IP (20 Bytes): Source and Destination IP of the physical servers.

- Outer UDP (8 Bytes):

- SRC Port: A calculated hash (this creates entropy so we can use multiple cables at once).

- DST Port: 6081 ( The port for Geneve).

Layer 2: The Magic Wrapper (The Overlay)

This is where the software-defined magic happens.

- Geneve Base Header (8 Bytes):

- VNI (24-bit): The Tenant ID. This ensures Coke’s data doesn’t leak into Pepsi’s network.

- Geneve Options (Variable, ~12-20 Bytes):

- This is the killer feature. eBPF inserts Metadata here.

- Example:

SecurityID=45912. The destination firewall doesn’t check IPs anymore; it just checks this ID. It’sO(1)complexity (aka: blazing fast).

The Math: Why Fragmentation Kills Performance

If your application sends a standard max-size packet (1500 bytes), look what happens when we wrap it:

Here’s the encapsulation overhead breakdown in a clean table format:

| Layer | Size Added | Running Total |

|---|---|---|

| Your App Payload | 1500 bytes | 1500 |

| Geneve Base | +8 bytes | 1508 |

| Geneve TLV Options | +12 bytes (average) | 1520 |

| Outer UDP | +8 bytes | 1528 |

| Outer IP | +20 bytes | 1548 |

| Outer Ethernet | +14 bytes | 1562 bytes |

The Problem: The standard physical internet cable has an MTU (Maximum Transmission Unit) of 1500 bytes.

The Result: Your 1562-byte packet hits the switch and gets dropped or fragmented (chopped into two). Fragmentation destroys CPU performance.

The Solution: You must enable Jumbo Frames (MTU 9000) on your physical switches. If you build a cloud without Jumbo Frames, you are trying to fit an elephant into a Mini Cooper.

Part 4: The Future - Where Are We Going?

We are moving away from “Smart Software on Dumb Hardware” to “Genius Hardware.”

1. Identity over IP

For 40 years, we allowed traffic based on Location (Source IP). “Allow 10.0.0.5 to talk to 10.0.0.6.” This is dumb because IPs change. The future is Metadata. The packet carries its own passport in the Geneve header. “Allow ‘Frontend-Service’ to talk to ‘Backend-Database’.” The network enforces this policy at line rate. We don’t care what the IP is anymore.

2. The Rise of the DPU (SmartNICs)

The “Tax” of the Matryoshka doll is CPU usage. Wrapping and unwrapping packets takes cycles away from your app. We are now moving this logic to DPUs (Data Processing Units) like NVIDIA BlueField. The server’s CPU doesn’t even know encapsulation is happening. The Network Card (NIC) handles the encryption, the Geneve wrapping, and the firewalling. It is a “free lunch” for application performance.

3. Quantum-Safe Overlays

Quantum computers will eventually break our current encryption. The beauty of flexible overlays like Geneve is that we don’t need to rip out cables to fix this. We just add a new “Option TLV” to the header containing Quantum-Resistant keys. We can upgrade the security of the entire internet just by changing the packet wrapper.

# Conceptualizing Hybrid Security in Geneve

class QuantumSafeOverlay:

def encrypt_packet(self, packet):

# We carry TWO locks on the packet:

return GenevePacket(

vni=packet.vni,

options=[

# 1. The lock we trust today (Fast, Standard)

TraditionalEncryption(RSA_encrypt(packet)),

# 2. The lock we need for tomorrow (Quantum-Resistant)

QuantumEncryption(Kyber_encrypt(packet))

],

inner_packet=packet

)

Conclusion: The Evolution Validated

The “Matryoshka Dolls” of modern networking aren’t just a neat trick; they are the only reason the internet hasn’t collapsed under its own weight. We have spent 25 years moving from physical cables to virtual lies, and we have the receipts to prove it.

If you scrolled to the bottom just for the summary, here is a quarter century of network engineering pain condensed into a grid:

| Era | Archetype | Representative | The Tech | The Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1995–2010 | Physical (Single Doll) | AOL | VLANs | “Rack Rewire” nightmares; engineers crying in server rooms. |

| 2010–2015 | Virtualization (Dual Doll) | eBay | VXLAN / OpenStack | 16M segments; we stopped caring about cables. |

| 2015–2018 | Scale Crisis (Heavy Doll) | Spotify | Kubernetes / CNI | 40% CPU overhead because we got greedy with encapsulation. |

| 2018–2022 | Optimization (Smart Doll) | eBPF / XDP | 10× performance; we taught the kernel to skip the boring parts. | |

| 2022–Present | Hardware Offload | AWS | Nitro / Geneve | “Bare metal” speeds; the hardware finally caught up to our software. |

The Bottom Line

For decades, we had to choose between Flexibility (Overlays) and Performance (Bare Metal).

- If you wanted speed, you dealt with rigid physical switches.

- If you wanted agility, you paid a “CPU Tax” to wrap packets in software.

That era is over. With eBPF optimization and hardware offloads like AWS Nitro, we have successfully paid down the technical debt. We can now wrap packets in three layers of metadata, route them based on identity rather than IP, and encrypt them against quantum computers all without the application feeling a thing.

The network has successfully abstracted itself. It is no longer a set of pipes; it is a programmable substrate that is just as fluid as the code running on top of it.

See the Matrix Yourself

Don’t take my word for it. If you have a Kubernetes cluster running Cilium, you can watch the dolls being assembled in real-time. Run this on any node:

# 1. See the eBPF programs hijacking your traffic

bpftool prog show

# 2. Watch the overlay traffic fly by (Standard Port 4789 or Geneve 6081)

tcpdump -i any udp port 4789 or udp port 6081 -vv